Filmikonkursi võistlustööd

Contestant 1

Annika Kluge (16), Helena Pass (16). Juhendaja Kadri Maaste

Tallinna Õismäe Gümnaasium

Annika Kluge (16), Helena Pass (16). Juhendaja Kadri Maaste

Tallinna Õismäe Gümnaasium

Osalejad: Argo Kangur, Hanna-Liisa Tamm, Eike Ambre, Neti Kukk, Melanie Olesk, Kristiina Kivari, Hele-Riin Udeküll, Salome Köb

Juhendajad: Merje Jürisalu, Jaan Prost-Kängsepp.

Elva Noorteteater

"Ühe naise lugu"

Jorma Bender (18), Madis Einama (18), Laura Raid (18),Rait Roop (18), Jaan-Sander Sillar (17), Elis Õis (18),

Juhendaja: Kristi Loit

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

"Hambaarst keskajal"

Autorid: Siret Samarüütel, Maris Graumann, Gerli Kruusmäe,

juhendaja: Aime Peever

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

Kaarel Kusmin, Kaia Kuusmann, Ilona Kuzmina, Karin Lipstuhl, Kristi Vilu, Eda-Kai Riim,Tanel Michelson, juhendaja: Aime Peever

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

Piia-Liisa Koll, Mari Västra, Kelly Roo, Kate-Eddy Tihamets, Hanna-Loore Hansen, juhendaja Aime Peever

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

"Ebajumalate ebakõla ehk põrgutee on sillutatud kaunite kavatsustega"

Autor: Merelle Paart, 17a,

Juhendaja: Merilin Paart

Jakob Westholmi Gümnaasium

Roland Ruul, Deivid Leppik, Oliver Ross, Ketter Lauri, Siiri Tamm, juhendaja Aime Peever

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

Gedrin Kreeps, Agnes Möldre, Elina Sahkur, Greta Maria Polluks, Kairi Lenk, Karl-Eerik Kokk, Kärol Järviste, juhendaja Aime Peever

Rapla Vesiroosi Gümnaasium

http://veebiakadeemia.ee/puramiidi-tipus/tehniline-kunstiajalugu/

Last week I (Grete Nilp) had a wonderful opportunity to spend 5 days in Copenhagen and visit different institutions and departments, which are dealing with conservation there. Also I had a chance to get a closer look to Copenhagen’s Christ Driving the Money-lenders from the Temple and met the painting’s lovely conservator Hannah, who gave me a great insight to different topics considering the conservation process.

First day – after getting lost in Copenhagen for a couple times I finally found Statens Museum for Kunst and met Hannah Tempest there. We had a tour around gallery’s conservation department and then looked trough different cross-sections from the painting. I really enjoyed Hannah’s explanations about different research methods and what kind of information is there to read out of the cross-sections.

In afternoon I had a chance to meet Jørgen Wadum, with who Hannah and I had a small discussion about different choices and decisions regarding to the conservation process, also how the famous author’s name (or a lack of it) affects viewpoints about an artwork.

Interestingly, looking at the four different underdrawings of the four paintings there were still some unnoticed nuances to discover, showing how versatile and different all the paintings really are.

Second day – started to make the climate frame for the painting with Mette Bech Kokkenborg and Hannah (painting will soon start it’s journey towards Estonia). This was my first time to see this kind of frame made, so this was really educational, also I had a chance to give a little helping hand also!

Main thing about this kind of frame is, that is seals the whole artwork (including polycarbonate backboard and safety glass) with a self-adhesive aluminium tape, so it creates stable climate within it.

Attaching the aluminum tape

Mette and Hannah are holding the painting, which is now in a climate frame (first version)

Third day – went to the Konservatorskolen, where I had a tour by Mikkel Scharff, the head of department. The school was truly remarkable, such good conditions for studying and doing research!

Amazing variety of pigments an the Konservatorskolen

Afterwards I spent some time in the conservation library (wow!), what a great collection of conservation literature.

Fourth day – had an opportunity to visit Nationalmuseet’s conservation department, located in beautiful Brede, which is a suburb of Copenhagen. Vibeke Rask from the department gave a really thourough tour. Interesting about the department is that it is using the old factory rooms, creating an unique atmosphere.

Fifth day – back in the Statens Museum for Kunst. As we learned, this kind of climate frame as we made on Tuesday wasn’t the best solution for such a big painting as Christ Driving the Money-lenders from the Temple (previously this kind of climate frame was used only on smaller paintings and it had worked out perfectly on them), pushing all the parts of the framing little bit too much together and making strip between the glass and painting too visible. So Hannah decided to go for a slightly different frame, as you can see here: http://www.smk.dk/en/explore-the-art/visit-the-conservator/stories-from-the-conservators/straightening-out-a-beautiful-queen/indramning/

(For the moment, painting is now safely and newly framed, ready for travelling. The photo is visible through BoschBruegelCPH Twitter account)

On afternoon I still had some time to look around in SMK, visit photo studio and look ehibitions, but soon it was time for goodbyes, as I headed back to the airport.

I want to say big thanks to everybody who I met during my days in Denmark, you’ve made my stay there really enjoyable and so interesting!

Now let’s count the days until the exhibition of the four paintings opens in Kadriorg Art Museum, Tallinn.

Since the beginning of the restoration Estonian version of the Christ Driving the Money-lenders from the Temple has been slightly different from other three paintings, because of the changes which have been made in the work’s composition by painting over some farm animals. By researching the underdrawing the animals are clearly distinguishable, they are finely modelled and artist has painted them with a clear role in the painting’s composition. Hiding them underneath the underdrawing raises various questions – was it made for better compositional balance or has it some kind of symbolic meaning? But if the pig carried some kind of message which needed to be hidden, then why paint only one pig and leave other one be? Or why cover donkey, an animal who plays essential part of Jesus’ entrance to Jerusalem?

It is known that covering of the animals took place quite shortly after finishing of the artwork, in the 17thcentury.

There are many overpaintings, which don’t come off so easily with a gel (which I mentioned in the previous post).

Probe from removing of overpainting on right side near sculpture (man with globe) on connection area of boards

Same problem revolves around hidden animals. Gel with usual ingredients doesn’t remove the overpainting from them and mechanical cleaning for such a big area needs much more time. It’s always possible to use more powerful ingredients in the gel (e.g. acetone), but it’s related to bigger risks, which doesn’t always pay off. So it's probably wise to leave the animals where they are until a better solution comes up.

Brownish spot - overpainting below Christ's leg

Interesting is that the overpaintings have turned out as a protective shield to the painting. Although they don’t get as much attention as an original painting, they carry interesting information. First series of overpaintings (in the 17thcentury) where made by a professional hand, showing that the painting was valued and important to it’s owner. Maybe then overpaintings should be more carefully examined and given more thought?

The British art-duo Jake and Dinos Chapman are currently exhibiting an artwork which includes a painting of the Crucifixion by a follower of Pieter Brueghel the Younger (c.1618), onto which they have made a number of overpainted alterations. Four years ago, before the Chapman Brothers bought the painting, it was sold for the equivalent of £39,000. Following the brothers’ acquisition of the work they made adjustments and additions to the painting by overpainting certain areas. The brothers infamously undertook a similar process with a series of prints by Goya, The Disasters of War, which became the basis for an artwork called Insult to Injury. The reworked Crucifixion painting forms part of a piece entitled Oi Pieter, I k-k-kan see your house from here. It is currently part of the exhibition Jake & Dinos Chapman: Jake or Dinos Chapman (15th July—17th September 2011, The White Cube, Hoxton Square and Mason's Yard, London).

As a work of art by the Chapman Brothers, Oi Pieter… recently sold for £750,000.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Oi Pieter, I k-k-kan see your house from here, 2011 (Source:http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/artsales/8646019/Jake-and-Dinos-Chapman-Heavenly-prices-for-Hell.html)

(Above left) Francisco Goya, from the Disasters of War series, 1810-20; (above right) Jake and Dinos Chapman, from Insult to Injury series, 2003

This story raises some interesting points about our—conservators’, art-markets’ and the viewing public’s—interpretation of the value of overpaint on works of art. This is particularly relevant in light of ongoing discussions about the various campaigns of overpaint in the different versions of Christ Driving the Money-lenders from the Temple. Of course, we should draw a clear distinction between the overpaint of restorers, and changes made by the Chapmans, who are re-presenting an Old Master painting in an entirely new context as a new work of art. However, the story caught my eye, and it leads us neatly into a discussion of the decision-making process involved in the removal—or not—of overpaint.

The discussion about the possible removal of overpaint which covers the animals in the Tallinn painting is touched upon in the blog post Video documentation of the conference "Techniques of Art History: Technical Art History" in Kadriorg. Anyone watching the video except in that post can see that there are strong and varied opinions among the experts present. This is partly to do with the fact that the question still remains: why were the animals covered? The knowledge that the underlying animals are in good condition at least suggests that it was an iconographic or aesthetic decision, rather than a damage-related one.

Overpainted goat in the Tallinn painting.

One of the most compelling arguments for removal of this type of overpaint is the aim of creating an ‘historically coherent whole’. However, these objects are bound to show traces of their 400-year existence in the form of changes/alterations; why not place value on this? It can come down to the function of the object. Decision-makers must think carefully and critically about why the object is of value. Why is it in a national collection? Is it because of its value as a cultural, historical object, or is its primary value as a painting, a picture? If the latter, then there may be an argument for removal of the overpaint. Crucial aspects of the decision-making and cleaning process are openness, dialogue and documentation.

Another instance of this type of decision-making came during the treatment of the Copenhagen painting. The large horizontal damage in the bottom part of the painting was heavily overpainted. The decision was taken to remove the majority of this overpaint. Why? Well, in this case, a number of factors came into play. Firstly, there was an aesthetic aspect to the decision: the overpaint was matched to a painting covered with discoloured varnish. Conservators felt that there was a great deal to be gained aesthetically by removing the varnish overall, but after varnish removal the overpaint simply did not match. The overpaint also covered a significant amount of original paint. There was also the fact that conservators understood why the overpaint had been added: an old treatment had resulted in an area of damage which the old restorer wanted to disguise. However, the fact that the old overpaint included some areas of invention and some iconographic changes was interesting. In this instance, it was felt that it was appropriate to document the old overpaint extensively before removing it and reintegrating the area based on our better knowledge of the methods and materials of the original painting and the other versions.

Overpainted area in Copenhagen paiting, before (top) and after (bottom) removal of old overpaint.

In the top-right of the Copenhagen painting, there were other areas of alteration and overpaint. The most obviously disfiguring of these were removed, again on aesthetic grounds. However, overall this area had been very overcleaned and abraded, and suffered from a number of dark spots, possibly related to staining of the protein-based ground. Two distant hills had been glazed over during a previous restoration campaign and changes to the architecture in this region altered the pictorial space and presented a complex problem. Cleaning tests suggested that there was very little original paint beneath the glazed hills; likewise, the building was very abraded. The level of damage, abrasion and staining in this area all contributed to a decision to retain some of the overpaint. True, this is not a historically coherent aspect of the painting, but the reality of removing overpaint from a very abraded area is that it would still require extensive retouching to reintegrate it, without gaining a great deal aesthetically or otherwise. In contrast, along the bottom panel join we revealed a significant amount of well-preserved original paint. Of course, both the decision-making and conservation processes are thoroughly documented in the conservation records.

This is only the tip of the iceberg, as far as the ethical and practical considerations of overpaint removal go. I believe we can look forward to a more detailed blog post of the treatment of the overpainted animals in the Tallinn painting soon. In the meantime, just imagine the complexities that will be faced by a future paintings conservator in 50 or 100 years’ time when presented with an object which is both the Crucifixion by a follower of Pieter Brueghel the Younger (c.1618) AND Oi Pieter, I k-k-kan see your house from here by Jake and Dinos Chapman (2011).

Cleaning process continues, as Alar is removing old varnish and overpaintings from the painting’s surface. With an each of my visit the changes are clearly visible – artwork’s colours become more vivid and truthful, revealing the staggering contrast between then and now.

On the surface of the painting there are all sorts of dirt, forming a “cultural layer”, which might give us a hint of the conditions where the painting has been. Besides dust there is human and animal hair, also tiny bits of coal – painting might have been in a room with an open fireplace.

Thick coat of yellowish varnish on left

At the moment, most efficient way for removing old varnish or overpaintings is a gel, consisting ethanol and isopropanol. It is applied for a brief time (about 30 seconds) on the chosen area and then removed (then varnish/overpainting comes off too). Bonus of the gel is that the work with this is finely controllable.

Overpainting

An interesting method which Alar used in earlier works before the gel, was so-called Pettenkofer method, invention by Bavarian chemist Pettenkofer and botanist Radlkofer. Idea is very simple – there is a little wooden box, fully opened on top, lined with cloth which is moistened with alcohol. Then the box is inverted and put on the painting, leaving it on a problematic area for a short time at room temperature to regenerate the varnish transparency or soften the layer what needs to be removed. Effect is similar to a gel, it softens the top layer of a varnish and makes it removeable. One problem is that the longer exposure time with vapour will touch the original painting. And of course, this box method leaves bright “square” of an activated area.

Overpainting

It’s known that back in time very different methods were used to clean the painting – micture of ethanol and turpentine etc, but before that acid of vinegar, lye and even animal’s urea were in use.

One problem next to old varnish and overpaintings, are the losses in painting, covered in unknown restoration with zinc white pigment (probably on the late 19thcentury). Massive paint cracks are visible on that kind of ground. In Alar´s experience of practice, he told, that he never saw before such restoration ground materials composition, and different publications noted that material which used was very rare.

Next time I’m going to talk about our animals under the cover and what’s happening to them.

Ultraviolet (UV) light has a wavelength shorter than that of visible light, but longer than that of X-rays. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, some materials used in paintings fluoresce.

Retouchings and over-paint applied on top of varnish show up clearly in UV as dark patches in an otherwise fluorescent area.

Traditional natural resin varnishes fluoresce a characteristic greenish yellow colour. It is therefore possible to monitor the removal of old varnishes.

This time we talked with Alar about first author traces of composition.

Underdrawing – first trace left on the undercoat, first visible sight of artist’s ideas and emotions, his style of working. Examination of an underdrawing has grown it’s importance over the 20thcentury and has now become one of the major elements of technical art history.

Infrared reflectography (IRR) helps to show underdrawing, passing throught different paint layers and giving a glimpse of artist’s initial thoughts, he’s vision of how the painting should turn out. Also it shows the material that was used to make an underdrawing – experienced eye differs charcoal in watercolour technique, silver, tin etc. Tallinn’s painting has traces of liquid and dry materials and one man’s hand was also sketched using quill.

Man's (with dark hat) hand was drawed with a quill (IRR)

Also it’s visible, that dry materials were used to draw architectural parts of the painting and liquid materials for figures. Underdrawing is very playful and quite sketchy, but it still does it’s job of forwarding those numerous emotions on people’s faces. Interesting is the fact, that adults are drawn with weary faces, looking sinful and haunted, while the children with their fresh and sincere emotions give them a nice contrast.

Artist has slightly modelled legs, arms and clothes of the people (IRR)

Artist(s) hasn’t bothered much to draw shadows, but has definitely slightly modelled figures with the line, giving them some form and shape.

IRR revealed that architectural parts were made with dry materials (IRR)

X-ray and examining of the foliation in the areas of the painting where paint loss has occurred, gives information about ground layer, which on Tallinn’s painting is a two-layered chalk-based coat, vertically brushed on the panel boards. It was laid on quite thickly (which on chalk-based undercoat ground layer is regular, cause it’s non-binding and hard to apply as a thin coat) and unevenly.

Thin white, slightly greyish coat of paint covers the underdrawing, it’s called imprimatura. It’s purpose is to protect the drawing and also give delicate tonal ground to the painting.

During the cleaning process, there are some parts of the painting, where the underdrawing comes visible on the surface, after the overpaintings are removed.

Continuing the story of Tallinn’s painting with Alar Nurkse.

In 2008 came a new era for our masterpiece. When 3 similar paintings were discovered in Europe, all with similar composition, new research began. Now, with modern technology available, X-ray and IRR scans were held, also dendrochronologial analysis.

Dendrochronological analysis (2008-10) revealed that the wood from the panel boards dates back to 1560-1575 (see more: http://www.bosch-bruegel.com/paintings.php?painting=tallinn&page=dendrochronology). Looking all the four works, it’s definitely noticeable the influence of Hieronymos Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder – some details in architectural part, similarity in types, simple emotions on faces and somewhat awkward poses – haven’t we all seen it before? But Bosch died in 1516 and Brueghel in 1569, so it’s definitely not the first and probably not the latter one too. But being one of the most popular artists in 16thcentury Low Countries, they had lots of followers, even centuries later. That’s a mystery what needs to be solved. Tracing hints like people’s haircut, fashion and even shape of everyday items, like a birdcage – they all may give us precious information about when the piece was painted.

UV shows us at first on painting’s surface it’s “cultural layers” – or some more or less overpaintings from last different owners in various sizes, also last coats of varnish.

Visibility with magnification of microscope got more understandable. Lots of earliest overpaintings were made to cover flyblows and paint losses. Varnish layer was thick – there was 3 or more different coats with colour and transparency changes. But varnish changes it’s colour over time, also it includes different components with resin, which sometimes may stay in little lumps on the surface of the painting. This all needs to be removed.

Detail of a infrared image, showing the underdrawing.

Infrared image showed painting’s sketchy underdrawing and X-ray revealed artwork’s inside, giving conservators valuable information, that the original painting is generally well-preserved.

X-ray

In 2010 came an opportunity to remove old varnish. What beautiful bright colours revealed from different parts of painting when the conservator had cleaned it!

Tallinn’s painting was partly overpainted, clearly visible are four different layers. But overpainting did not just cover flyblows or correct paint losses – there is a fine amount of farm animals which the infrared image revealed. Two pigs, a goat and a donkey, all have been covered with paint by an unknown hand (see more: www.bosch-bruegel.com/paintings.php?painting=tallinn&page=infrared). Reason is unclear, one idea is that is just a compositional trick to balance dark areas of the painting. But doesn’t that create some misunderstanding – for example, a man, who has his hands open wide, definitely to catch a lovely pig, is now oddly spreading his arms to the darkness. And the pig was painted perfectly fine as the infrared image and x-radiograms shows!

Detail, where partly cleaned area is visible (lower left corner shows the thick varnish coat)

At the moment, Alar is removing little bits of the overpaintings and old varnish with gels and solvent mixtures, also mechanically cleaning painting from flyblows. These processes are quite time-consuming and are raising lots of questions, but they’ll also bring answers, which must be analytically observed. Some of overpaintings didn’t reveal on the first UV-scan (because of a thick varnish-layer) and have exposed over cleaning process, so scans must be held regularly.

Doesn’t every layer bear in itself a piece of painting’s history? How to separate important and “talking” trace from unimportant, that’s a conservator’s daily task to solve.

Dendrochronology is a method used to identify the formation time of growth rings in wood by measuring the distance between the rings. Good growing conditions produce wide growth rings, while poor growing conditions produce narrow rings. The pattern formed by tree rings of varying thickness is therefore typical for a certain period. The seasonal changes in our northern climate cause the very clear growth pattern typical for oak. In dendrochronology it is possible to determine the precise felling date of the tree down to the exact season of the year in which the tree was felled (see more: http://www.bosch-bruegel.com/paintings.php?painting=tallinn&page=dendrochronology).

Before the Bosch-Bruegel research project began, the Copenhagen painting had not been in the conservators’ workshop for a major treatment for almost 50 years. The most recent, mid twentieth-century treatment focussed on the consolidation of flaking paint, and the conservators did not clean the painting at this stage.

When we came to assess the painting in the early stages of the project, before the current conservation treatment began, one of the first things that we noticed was the very thick and extremely discoloured varnish which coated the paint surface.

[fig.1] Greta Koppel and Alar Nurkse inspecting the Copenhagen painting at the National Gallery of Denmark

It is normal for paintings from this period to have a varnish layer. The varnish that was present on this painting before treatment was not the original varnish, but one which was applied by a restorer during a previous treatment. The role of the varnish is to sit on top of the layers of paint and saturate the surface – like a wet pebble from the beach, which looks paler and more matt once it dries. However, the once-clear varnish on this painting had degraded and become a deep yellow-brown colour, which shifted the tonality of the painting and made the whole image appear brown. The varnish had also developed a network of fine cracks which gave the painting a hazy appearance [fig.2].

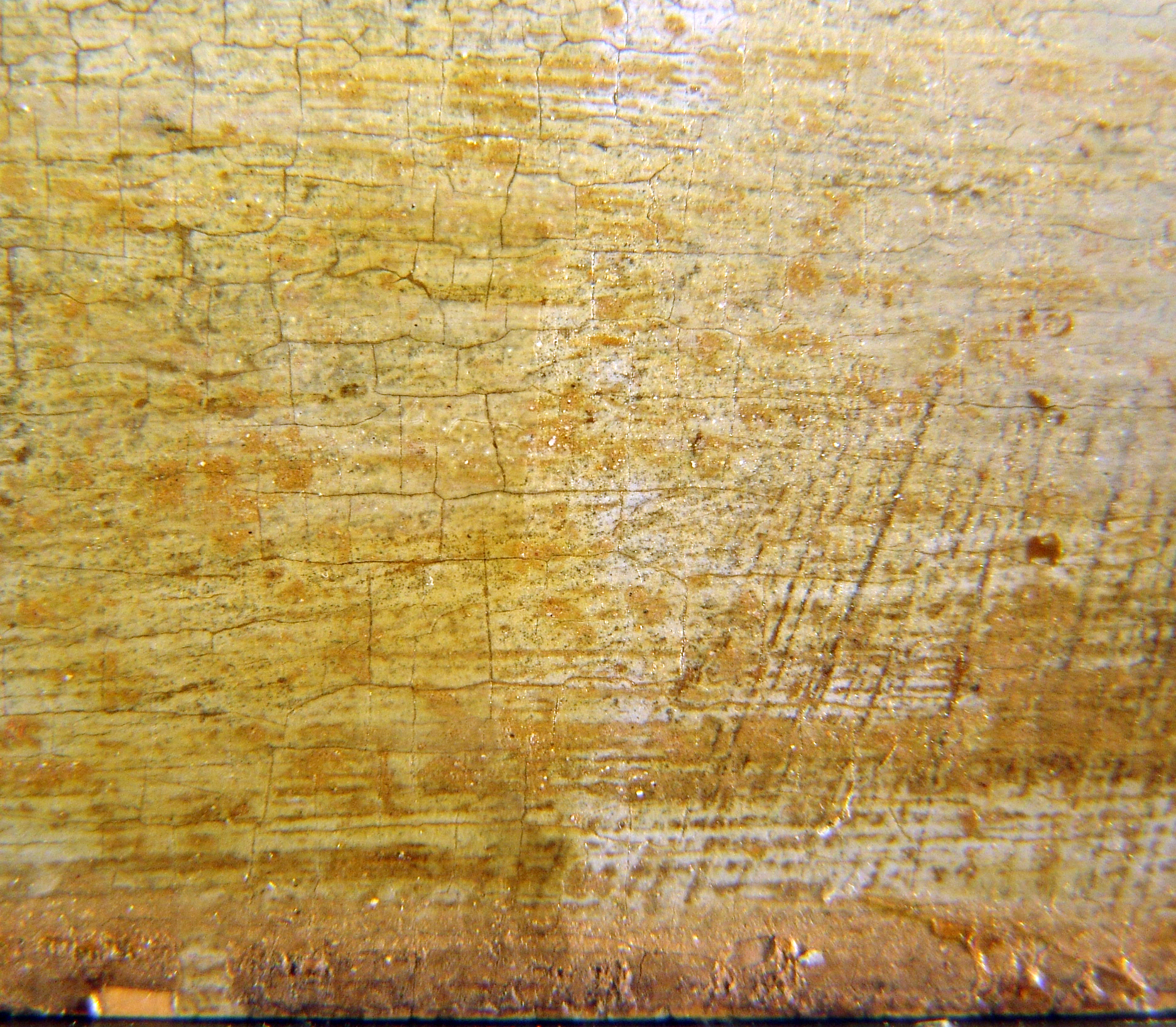

[fig.2] Photomicrograph (x6.4) before treatment showing discoloured and cracked varnish over one of the central figures

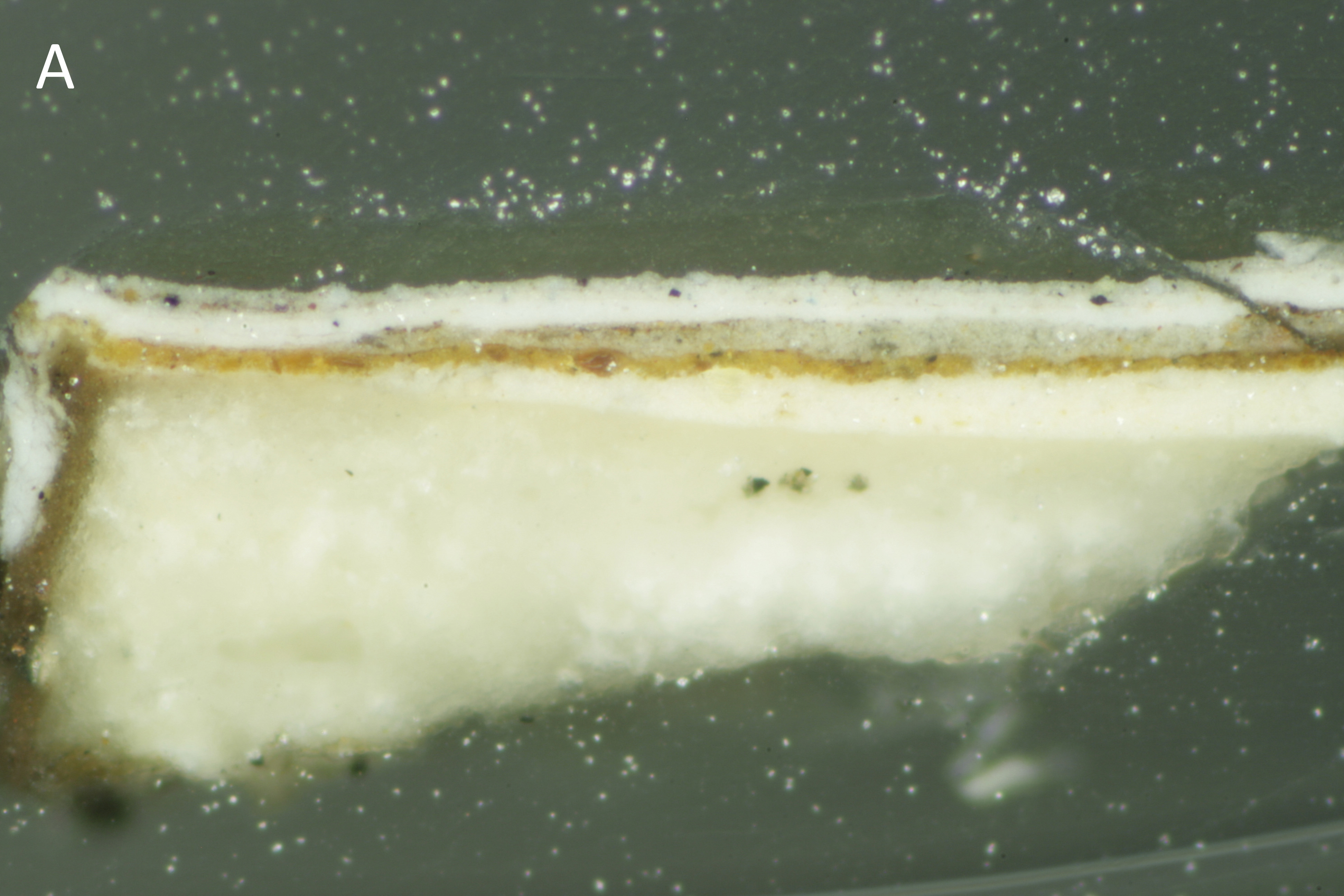

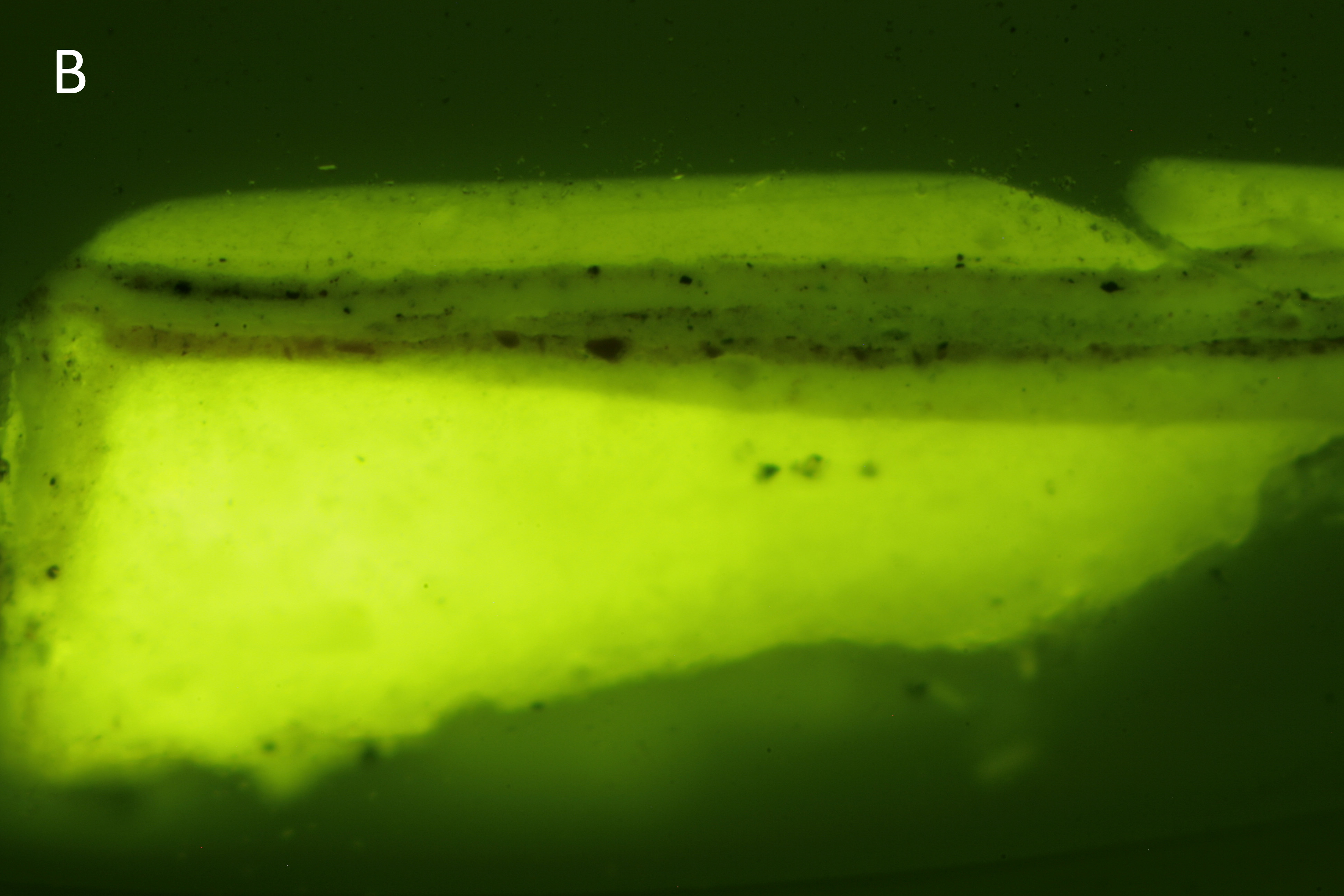

Over the decades, maybe even centuries, successive applications of varnish had been applied over one another, meaning that the varnish was actually composed of several layers. As part of the analysis of this painting, the layer structure and composition of the varnish were characterised. The different layers of varnish can be seen in cross section in ultraviolet (UV) light [fig.3]. The greenish appearance of the varnish in UV suggests that it is a natural resin. GC/MS carried out on our behalf at the National Museum of Denmark further identifies it as colophony with a small amount of poppy-seed oil, and trace amounts of beeswax in the upper layer.

[fig.3] Cross section from the headdress of the woman in the centre of the painting, photographed at (x250) in [A] normal light and [B] in UV light, showing the different layers of varnish at the top of the photograph

After the painting was surface cleaned with an aqueous solution to remove the dirt that was present on top of the varnish, tests were carried out with a range of cleaning systems with the aim of establishing the best solution to remove or thin the varnish in an effective yet controllable way [fig.4]. Varnish becomes more difficult to remove as it ages; therefore, the lower layers of older varnish were more difficult to remove than the youngest, upper layer. Solvent cleaning achieved the best results in initial tests, and so a further series of tests of solvents and mixtures was undertaken.

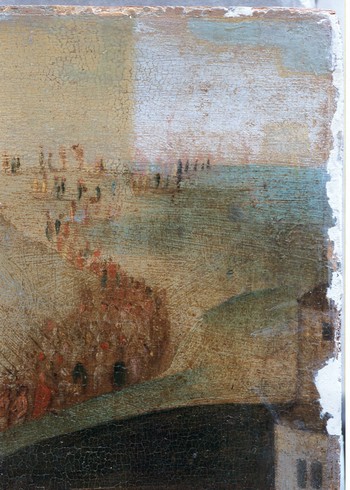

[fig.4] During varnish removal; a series of varnish tests is visible in the sky along the top of the photograph

[fig.5] Varnish removal in progress

The most appropriate cleaning system was established. This was actually a combination of two solvent mixtures which were applied sequentially, the first through tissue paper, which held the less volatile solvent on the surface like a simple poultice allowing it to swell the old degraded varnish, and the second which was used later to remove uneven residues of varnish.

[fig.6] Detail of the face of one of the traders during varnish removal

The removal of varnish has allowed the bright colours and fine details of the painting to be seen once again, but it has also revealed various old damages which were disguised by the varnish or hidden under old overpaint. These will be reintegrated during a later stage of the conservation-restoration treatment.

[fig.7] Detail of the Temple interior after varnish and overpaint removal

-- Hannah Tempest, Statens Museum for Kunst

From 13th to 14th of May annual Kadriorg Art Museum’s spring conference took place. This time the conference focused on technical art history, called Techniques of Art History: Technical Art History.

Specialists from different countries discussed topics about art, it’s material and how it helps us to interprete the artwork.

Full program of the conference can be viewed here: http://www.bosch-bruegel.com/?page=conference

One of the event’s main theme was Tracing Bosch and Bruegel international research project. During the second day of the conference, workshop and discussion were carried out, focusing on four versions of Christ Driving Money-lenders from the Temple and what kind of similarities and differences they have. Here you can follow the discussion via video documentation.

To reveal or not to reveal the hidden animals of Tallinn painting?

One of the topics was the dilemma: to reveal or not to reveal the overpainted animals (including two pigs, a donkey and a goat) of Tallinn painting: does the overpaintings have an historical value, what are the ethical dilemmas of the decision etc. (see more about the overpaintings: http://www.bosch-bruegel.com/paintings.php?painting=tallinn&page=infrared

As Alar Nurkse is just starting to carry out the trials to remove the overpaintings, we upload a short video clip of the discussion during the workshop.

Hello! This is Hannah, from the National Gallery of Denmark. Today I'm going to be blogging about the structural conservation of the Copenhagen painting, but before delving into the details of the recent structural work, I will fill you in on the story of how the wooden panel came to need the attention of conservators in 2011.

The original wooden panel of the Copenhagen painting is made up of 4 pieces of oak, all from the same tree, which was cut down in the Baltic in the 1560s. In the past, restorers and craftsmen have carried out various treatments to modify the support of the painting.

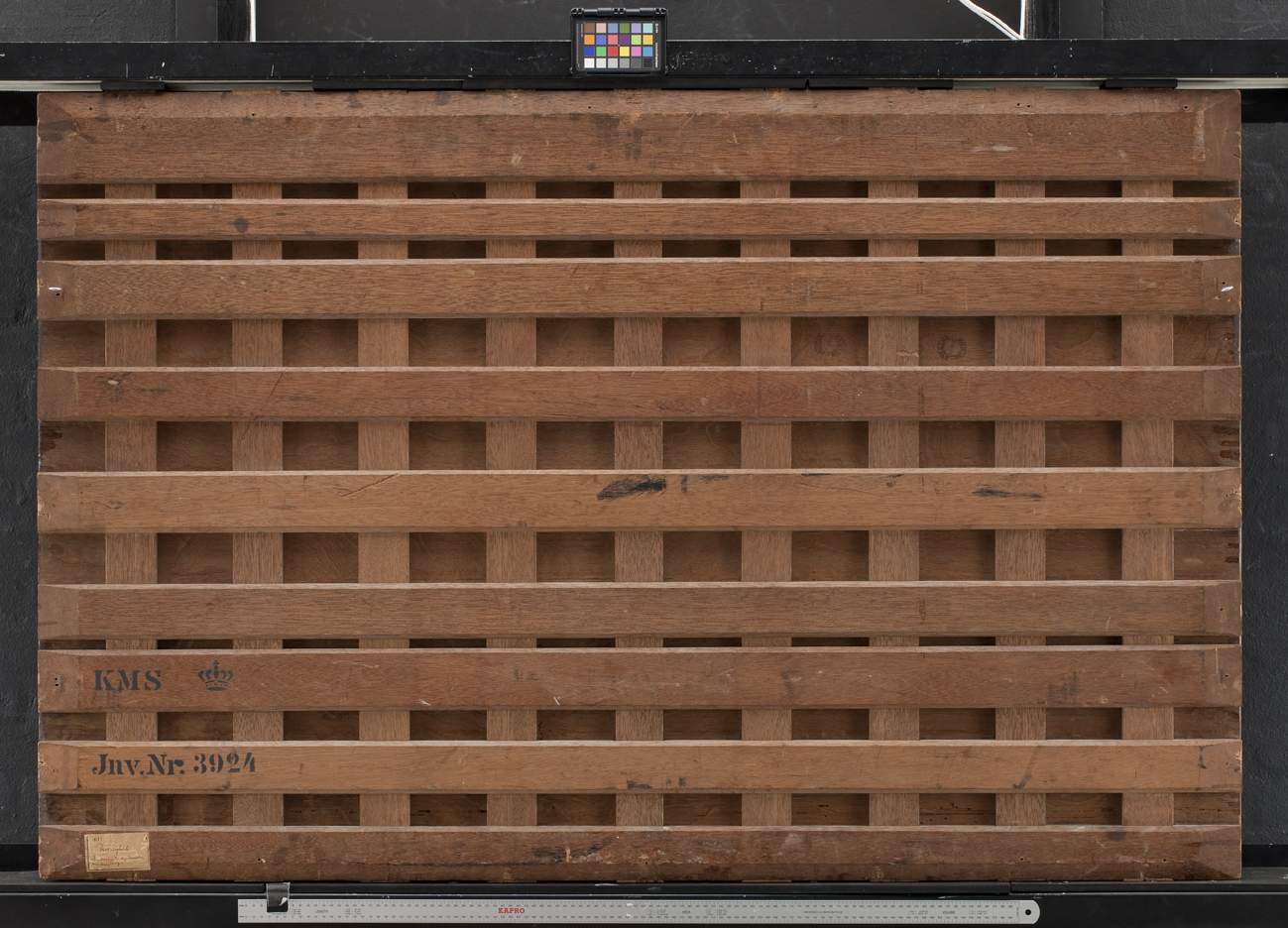

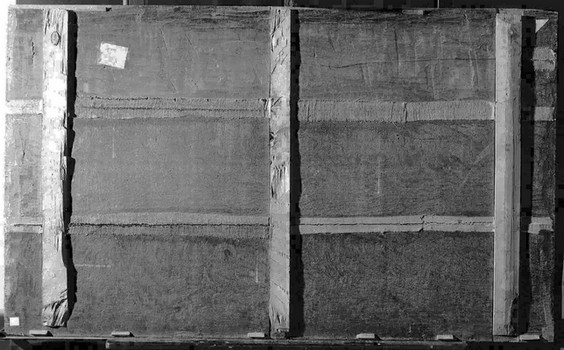

[fig.1] The back of the Copenhagen painting before treatment - December 2010

The panel was thinned at some stage (but not as dramatically as the Glasgow painting which was thinned to less than 3mm in the past!), and at some point the lower part of the panel came apart and was reattached. This treatment (the likes of which would not be carried out now) involved drilling through the wood and paint, in order to attach a supporting batten to the back. At the same time, the front of the painting was planed down to make it flat, because there was a little 'step' between the two parts of the panel, which unfortunately resulted in a paint loss in this area [fig.2].

[fig.2] Partway through varnish-removal, with damage to bottom panel join visible at left side

This supporting batten was long gone before the present treatment was carried out, and had been replaced with a lattice structure attached to the back of the painting known as a 'cradle' [fig.1]. The cradle had seized up, resulting in a thick, heavy and completely rigid backing. Although the cradle was attached to the painting by past restorers with the best of intentions, it is no longer considered to be beneficial to the original structure; in fact, before treatment, the painting had an unusual concave warp, which was possibly related to the cradle, and there were various splits which may have been exacerbated by this structure.

We wanted to reduce the thickness and weight of the cradle, but were keen to keep some level of support for the original panel which had joins, splits and other weak points. We first removed the mobile battens, and then our National Museum colleagues, Birgitte Larsen and Bodil Holstein, were able to use woodworking tools to thin the different parts of the cradle to pre-set depths, decided beforehand [fig.3]. The moveable battens - also thinned and modified - were reattached in their old positions with flexible metal clamps, which were screwed into the remaining cradle blocks.

[fig.3] National Musuem conservators using hand tools to thin the old cradle

This treatment has improved the flexibilty of the auxiliary structure, which we feel is now more sympathetic to the original painting, as well as being lighter-weight and more practical for handling and transportation. The modified system still provides support for the original panel which has joins and weak points [fig.4]. It also allows us better access to the back of the original panel which is important for research. All of this has been achieved by modifying only the unoriginal backing, not the original 16th-century panel, and of course, the process has been documented fully.

[fig.4] The back of the Copenhagen painting after treatment - March 2011

This is the first post from Estonia!

The responsible job of blog writing is brought to you by me, Grete, an art history graduate and currently an enthusiastic freshman in Estonian Academy of Arts, hoping to become a painting conservator myself someday. My work is to do the best to forward the words and doings of Alar Nurkse, main conservator working on Christ Driving Money-lenders from the Temple and also to give a glimpse of my own thoughts.

The year was 1999 when the conservation story for our painting began. Kadriorg Art Museum was going to exhibit new exposition in a freshly renovated palace next year and all the art conservators were in a big hurry to get ready with all the works.

The year was 1999 when the conservation story for our painting began. Kadriorg Art Museum was going to exhibit new exposition in a freshly renovated palace next year and all the art conservators were in a big hurry to get ready with all the works.

Christ Driving Money-lenders from the Temple brought up many questions, but the time was short and museum lacked of necessary research equipment. Because of those reasons it was all down to essentials procedures – to maintain durability of the panel and to correct few smaller damages on the painting.

Main problem was the panel – old battens were glued on the wood, looking kind of robust. It was also certain that these were added to panel’s backside later, probably on the late 19thcentury. With removal of the battens it was assured that the panel wood was able to “breathe” again.

Backside before restoring

The joints of the boards were covered with fabric strips. New supporting system was made, this time following the example of 1970s Florentine method, using so-called “puppies” (little wooden bricks which hold battens on their place) and not glue. When old fabric strips were removed, some pieces of Italian newspaper came out, which might indicate to the region where painting in the 19thcentury was restored.

Backside with new battens and "puppies"

In 1999 there was too little time to completely remove yellowish-brown varnish, but small “window” was still opened on the right upper corner of the painting. Many different layers of the painting were visible there, giving a hint what could artwork look like when completely cleaned. But the time wasn’t ready yet, painting had to wait for a decade for more close studies.

Detail of a corner, where cleaned area is visible

The Bosch-Bruegel research project involves the conservation and restoration of both the Copenhagen and Tallinn versions of Christ Driving the Money-lenders from the Temple. Conservation of the two paintings is currently in progress and is being carried out by Hannah Tempest at the National Gallery of Denmark and Alar Nurske at the Kadriorg Art Museum. The conservation of the paintings is being undertaken within the context of the research project, and conservation decisions are guided by invaluable input from members of our international team of conservators, conservation scientists, curators and art historians.

XRF - one of many analytical techniques used by our team

So far, the Copenhagen team has been posting about the exciting discoveries and day-to-day activities of the conservation process on Twitter. In addition to this, conservators and curators from Tallinn and Copenhagen will now be blogging about the conservation of the two paintings. The aim of the blog is to share information about the conservation process with you as it happens, and to offer an insight into the important work that goes on behind the scenes of our museums and galleries as conservators work hard to preserve our shared cultural heritage.

The Copenhagen painting during varnish removal - Spring 2011

As we begin the blog, the removal of the old, discoloured varnish which was obscuring the Copenhagen painting is nearly completed. The next step will be to fill in old losses in the paint film, before applying a new varnish to saturate the surface. Then the challenging work of retouching the painting can begin!

In April 9, 2011 Peter van den Brink, an expert on 16th century Netherlandish painting paid a visit to the Art Museum of Estonia. During his visit he showed a special interest to the ongoing Bosch & Bruegel research project. Brink, himself a student of Dolf van Asperen de Boer, the founder of Infrared Reflectography has used the material analysis in several of his curated projects, of which the exhibition The Brueghel Enterprise (2001–2002, Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht and Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten Brussel) is the most renown. The exhibition together with its catalogue set a standard for a scientific approach and serve as an excellent example of the technical art history discipline.

Peter van den Brink is an internationally renowned art historian, specialising in the Netherlandish art of the 16-17th century.

Since 2005, Peter van den Brink has been the director of the Aachen City Museums, and previously worked as the chief curator of the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht.

Tracing Bosch and Bruegel: Four Paintings Magnified is an exciting pan-European art detective scenario investigating four Netherlandish paintings from the 16th century.The busy compositions all present ‘Christ chasing the moneylenders from the temple’ and reuse popular iconography influenced by the famous painters Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Read more...

Keep an eye on us

Facebook

Twitter